The killing of seven revolutionaries -The Asian Age

Tusar Talukder comes across a darkened chapter of our political history

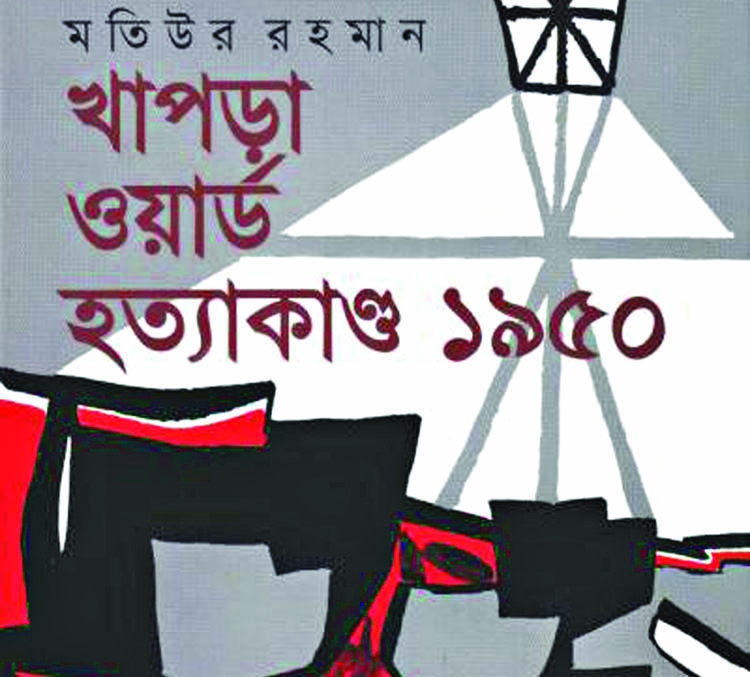

Matiur Rahman's Khapra Ward Hotyakando 1950 is a record of political history, quite unknown to many of us. De facto, the assassination took place in Khapra Ward of the then Rajshahi central jail on April 24, 1950 and is considered the first jail killing in undivided Bengal. On that day, the firing by the police took lives of seven communist revolutionaries and seriously wounded at least 32 revolutionaries.

No particular reason was known about this sudden firing by the police. After five decades of the assassination, Matiur Rahman, a veteran journalist of Bangladesh and the Editor of the Daily Prothom Alo, has tried to find out the possible reasons behind this killing through his research work. Indeed, I would like to consider this book of Matiur Rahman a complete research work rather than a mere book of history because while writing the book, he, like a researcher, has undergone a long process which involves taking interviews, collecting necessary information from different places of Bangladesh, West Bengal and Assam, and going through the books and journals containing write-ups on Khapra Ward Killing. He has given a chronological account of the incident.

Matiur Rahman has divided the book into six chapters which give the readers a complete view of Khapra Ward killing in 1950. The first chapter describes the seven martyrs of Khapra Ward and how some comrades remembered the martyrs and the wounded prisoners in many of their writings and speeches. The second chapter entitled "Seven Martyrs of Khapra Ward: Jail's Condition and the Revolution of the Political Prisoners" denotes the deteriorated condition of the jail and different stages of the revolution of the communist revolutionaries. This part also discusses the ill-treatment of the then Rajshahi jail authority of the political prisoners.

Through his analysis, Matiur Rahman shows how the prisoners were deprived of their basic rights. The third chapter, a very substantial one, focuses on how communist revolution turned from a non-violent resistance to a violent and armed one. Having been influenced by the plan and programmes of the then Indian Communist Party, East Pakistan Communist Party took the decision to conduct an armed revolution countrywide. Consequently, the political prisoners were taking preparation for a jail-revolution.

As a part of their preparation, they took part in a starvation program called by the then general prisoners of Rajshahi jail. Furthermore, the political prisoners were preparing themselves for a violent and armed resistance by doing different kinds of physical exercises. The author of this book opines that all the aforementioned things agitated the jail authority of Rajshahi. In a word, the decision of armed revolution within the jail and outside enforced the jail authority to take a barbaric decision of killing. The main motto of this killing was to shake the basis of communist revolution.

The fourth part of the book describes the events of 24th April, 1950. Most of the veteran political prisoners were transferred to separate wards. As a result, they expressed their deep dissatisfaction. Also, some of them denied to be separated from one another. Following the direction of the then Rajshahi Jail Superintend, the police transferred some of the prominent political prisoners who belonged to the Communist Jail Committee to Khapra Ward in Rajshahi jail. The fifth chapter provides readers with the events of 24th April. The prisoners did not have an iota of idea that the police would open fire on them.

On 23rd April, 1950, some of the members of Communist Jail Committee planned to keep Jail Superintend locked in his office room unless the then Government of East- Pakistan fulfilled their demands. But before the execution of their plan, the Superintend got out of his room. On the other hand, some of the political prisoners were locked inside Khapra Ward. Afterwards, the prison guards following the order of the jailer opened fire on the prisoners. The police firing killed seven leaders while 32 of them were seriously wounded. The last chapter of the book analyzes the manifold impacts of Khapra Ward Killing on other political prisoners.

Matiur Rahman's initiative uncovers a darkened chapter of our political history. It points fingers at the wrongdoings of the then Communist Party. It throws light on the unknown chapters of our history. And no doubt, Khapra Ward Hotyakando 1950 sharpens our historical as well as political sense. Overall, this book has added a new dimension to the political history of the Communist Party.

The reviewer is a critic and translator. He teaches English at Central Women's University. He can be reached at [email protected]

The reviewer is a critic and translator. He teaches English at Central Women's University. He can be reached at [email protected]