Published: 09:55 AM, 28 November 2025

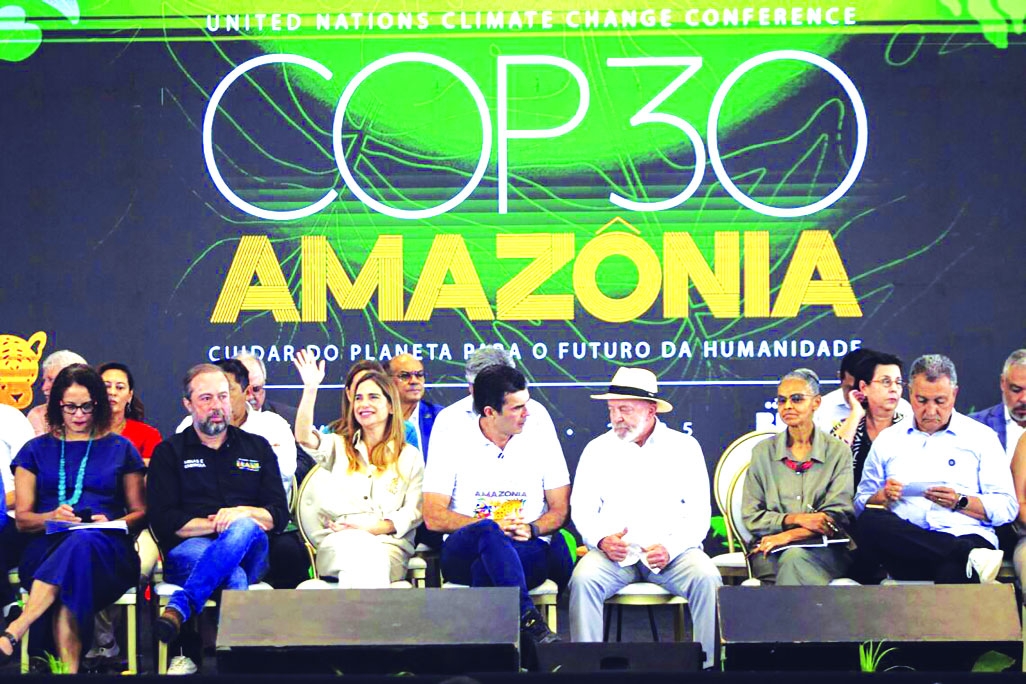

Belém’s Promise and Frustration: What COP30 Meant for Bangladesh

Dr. Shahrina Akhtar

As COP30 concluded in Belém, Brazil, Bangladesh’s delegation returned home carrying a blend of hope and frustration. For a nation already living through the harshest impacts of climate change, cyclones, tidal flooding, salinity intrusion, and erratic rainfall, the stakes at this year’s summit were exceptionally high. Bangladesh welcomed the progress made on adaptation and equity, yet the failure to secure a clear global commitment on phasing out fossil fuels cast a long shadow, raising doubts about the world’s willingness to protect its most vulnerable communities.

Adaptation and loss-and-damage financing offered the strongest gains for Bangladesh. Countries agreed to double adaptation finance by 2025 and triple it to US$120 billion annually by 2035, a major step toward closing the adaptation gap that Bangladeshi negotiators have repeatedly emphasized. Progress on the Loss and Damage Fund was equally significant. COP30 opened direct-access windows allowing vulnerable countries to receive US$5–20 million annually, an important shift, even though the fund currently holds only US$756 million in pledges. These steps suggest that countries like Bangladesh may soon access critical funds more efficiently during climate disasters.

Momentum also grew around equity. COP30 strengthened its Gender Action Plan, requiring gender analysis, desegregated data, and deeper integration of gender equality into climate strategies. The summit also endorsed a new Just Transition Mechanism, aimed at protecting workers, Indigenous Peoples, and marginalized communities as countries shift to clean energy. For Bangladesh, this is a crucial recognition that climate action must be socially just and inclusive. Yet the absence of any explicit fossil fuel phase-out language dampened these gains, leaving Bangladesh questioning whether global ambition is enough to match the scale and urgency of the crisis it faces daily.

Fossil Fuel Deadlock and Diplomacy: While adaptation gained momentum at COP30, the issue of fossil fuels quickly became the biggest stumbling block. Despite strong support from more than 80 countries for a clear phase-out plan, the final text avoided any mention of ending coal, oil, or gas. Major producers such as Saudi Arabia, Russia, and India resisted firmly, insisting on their sovereign right to keep extracting fossil resources.

For Bangladesh, this outcome was a major letdown. Civil society groups like the Bangladesh Working Group on Ecology and Development (BWGED) had pushed for a just and fair transition, backed by grants, technology support, and a move away from what they call “false solutions” such as carbon capture or nuclear energy. They wanted clarity, ambition, and a timeline, but the roadmap never materialized.

The deadlock was political as much as technical. Developed and vulnerable nations remain divided over responsibility, timelines, and financing. Bangladesh warned that without accessible, grant-based support, a just transition risks becoming an unfair burden on countries least responsible for the climate crisis.

Technology, Institutional Hurdles, and Disappointments: Another area of concern for the Bangladeshi delegation was the lack of concrete technology transfer commitments. Despite calls for accelerated access to renewables, especially solar, wind, energy-storage, and grid modernization, countries remained deeply split. Bangladesh negotiators voiced frustration that technology support was vague, underfunded, and not clearly framed as a global public good.

Adding to the urgency was the fact that Bangladesh’s National Adaptation Plan (NAP) for 2023–2050 estimates a financing need of roughly US$230 billion, a figure impossible to meet without consistent, predictable international support. And as Bangladesh transitions away from its Least Developed Country (LDC) status, it insists on maintaining easy and equitable access to key funds such as the Green Climate Fund and the Adaptation Fund.

The Fire, the Fractures, and the Framing of Equity: COP30’s drama was not limited to negotiations. A fire broke out inside one of the pavilions in Belém, forcing delegates to evacuate in a tense moment that underscored the physical fragility of the summit itself. Mirroring the politics, the fire became a metaphor for the summit: well-intentioned but volatile, perhaps too fragile to contain the pressures burning beneath.

Indeed, multiple reports suggest that powerful fossil-fuel lobbyists were deeply embedded in the talks, raising questions about the influence of corporate interests at the heart of the negotiations. Meanwhile, the COP30 presidency, under Brazil, suggested its own failure to deliver unambiguous fossil fuel language, citing waning enthusiasm among richer nations.

Reflecting on Bangladesh’s Gains and Risks: For Bangladesh, COP30 in Belém represented both promise and peril. On one hand, the financing pledges for adaptation and the operationalization steps for the Loss & Damage Fund offer hope. These could enable Bangladesh to scale up critical resilience projects, coastal embankments, salt-tolerant farming, rainwater harvesting, and more, that are already part of its adaptation planning. Civil society leaders called for those improvements to be backed by grant-based funding, not loans, underlining the risk of debt traps.

The newly codified mechanisms for gender-responsive climate action and a just transition show that the world is starting to grasp the social dimensions of climate change, not just the environmental ones. For a frontline country like Bangladesh, these equity gains are more than policy successes; they are survival strategies.

Yet, without a fossil fuel phase-out roadmap, the long-term trajectory remains worrying. As Bangladesh pushes for an energy transition, the global absence of a clear exit strategy from fossil fuels means the country may remain exposed to markets, subsidies, and systems that perpetuate emission-intensive pathways. This could undermine its ability to leapfrog directly into clean energy, and risk saddling it with expensive technologies or debt. The void in technology transfer is particularly stark. Without committed finance for clean energy infrastructure, Bangladesh’s low-carbon ambitions may stall, or worse, be compromised by reliance on debt-heavy pathways.

Finally, institutional trust remains fragile. The visibility of corporate lobbyists, the lack of transparency in fund governance, and the absence of binding commitments all fuel skepticism among civil society and negotiators alike. There is a real risk that the promises made in Belém could remain on paper if implementation mechanisms are weak or under-resourced.

Strategy and Hope for Bangladesh: Looking forward, Bangladesh must convert the diplomatic gains of COP30 into domestic action. This requires building stronger institutions to absorb climate finance, developing robust bankable projects for adaptation and energy transition, and ensuring transparency in how funds are accessed and spent. Realizing the NAP’s goals will need not just ambition, but technical capacity, accountability, and sustained diplomatic pressure.

At the same time, Dhaka should continue to leverage its voice within coalitions, the LDC group, G77+China, and other frontline nations, to insist that developed countries deliver on grants, not loans; to demand real phase-out pathways for fossil fuels; and to ensure that technology transfer is not conditional or superficial, but real and scalable.

Civil society in Bangladesh will remain critical. Groups like BWGED have already set a high bar with their demands for a just transition, fossil fuel exit, and grant-based climate finance. Their engagement (alongside youth representatives, gender advocates, and grassroots communities) will be key to holding both national leaders and global partners accountable.

But perhaps the most important reflection is this: Bangladesh is no longer just a victim of climate change, passively calling for help. In Belém, it asserted its role as a moral and political leader demanding justice, equity, and ambition. That voice matters.

COP30 may not have delivered everything Bangladesh asked for, but it offered a clear mandate: adaptation must be at the center, climate finance must be fair and accessible, and transitions must be just. How Dhaka channels that mandate into real change in the coming years could define not just its own climate future, but a model for frontline nations everywhere.

Dr. Shahrina Akhtar is a Research Coordinator and Assistant Professor at the Institute of Development Studies and Sustainability (IDSS), United International University (UIU), Dhaka.