Published: 12:36 AM, 12 October 2017

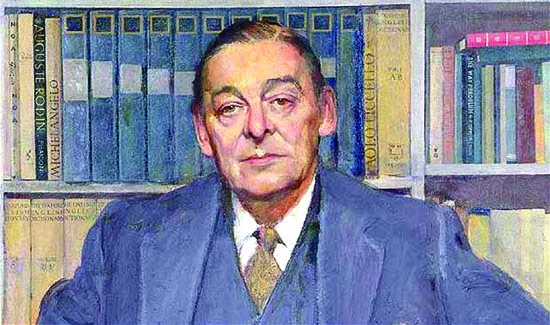

T. S. Eliot in the words of Lyndall Gordon

T. S. Eliot

T. S. Eliot Lyndall Gordon was born in Cape Town, South Africa in 1941 but she has been in the United Kingdom for several decades and working at Oxford University as a Senior Research Fellow in the field of literary biographies. She has so far written a broad spectrum of books on Emily Dickinson, Charlotte Bronte, T.S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf excavating the personal as well as the literary feats of these authors and poets.

Lyndall Gordon

T.S. Eliot: An Imperfect Life is a compendious book by Lyndall Gordon on T.S. Eliot's personal life, his literary creations and some remarkable events in his life which had remained hidden to most of the readers before Lyndall Gordon took a deeper look into the memoirs and works of this eminent poet. In this voluminous book of 752 pages, T.S. Eliot has been explored as a poet and as a man too whose life was described by different analysts earlier in a way that contained broad abstractions but those textual attempts offer a very limited space to conveniently untangle the puzzles of T. S. Eliot's verses and expressions.

T.S. Eliot, during his lifetime, did not authorize anyone to write his official life-sketch. He had a deeply cloistered and recluse personality. Loneliness attracted him more than company most of the time. And he cautiously kept his thirty-year long romance with Emily Hale, who believed that he loved her and would marry her afterwards. The relationship retained its steam even after Eliot denied marrying Emily when his first wife, Vivienne, died in 1947. But he ended all ties with Emily in 1956 and it is thought that, at the same time, he destroyed all the letters exchanged between him and Emily. Few people knew about this until Lyndall Gordon began exhuming the remnants of Eliot's past.

Others who believed themselves to be close friends, like Mary Trevelyan and John Hayward, his "two closest friends from the late forties to the mid-fifties", also came to realize how little they really knew Eliot. Yet, Lyndall Gordon, picking up Eliot's poetry and plays as her guide and consulting as many primary sources as she could discover, has done a superb job of writing a biography of this introverted, abstruse, imperfect and sentimentally driven man.

Gordon began her research in 1970. Her first book, Eliot's Early Years, was published in 1977 and its sequel, Eliot's New Life, in 1988. This present book is the result of further research and new investigations, including new access to Eliot's manuscripts; classified letters about Eliot written by Emily Hale to close friends; Mary Trevelyan's unpublished memoir of her close friendship with Eliot; and a bundle of Eliot's letters which were recovered from an English pig farmer who was about to burn all those precious stuffs.

I did not read Lyndall Gordon's earlier books, so, some details in this book were new to me. I am filled with admiration and wonder at the superb job she has done in resurrecting Eliot's life through his poetry and plays in an easily comprehensible, insightful, sensitive and objective style. It helps if the reader knows Eliot's poetry fairly well, but this is not essential and in many cases Gordon's comments elucidate Eliot's poetic diction and make his poetry more accessible to the general readers.

Lyndall Gordon points to two great moments in Eliot's life as the source of his lifelong quest: a moment of silence on a Boston street in 1910, when he was suddenly convinced that "life is justified"; and a similar moment years later in the Rose Garden at Burnt Norton. These fleeting apprehensions of something beyond the chaotic flux of daily life, working on a man whose ancestry, upbringing and education had fostered the religious and philosophical side of his character, came to dominate his life.

Through his poetry, he struggled for a closer understanding of life and for blitheness. And his Puritanical zeal - his distaste for worldly things - made him a sharp adjudicator of the conspicuous perils of the twentieth century. For many who perused his poetry, and those were amazingly popular, he had a prophetic vision denigrating the absurdities which surrounded the initial years of 20th century.

Lyndall Gordon does not dig much deeper into Eliot's anti-Semitic bent. She comments that "biographers, of all people, know it is naive to expect the great to be good". And she points out that, although being anti-Semitic is often considered to be "a commonplace of the time", other writers of Eliot's milieu "countered it in different ways". She refers, also, to his misogyny, his lack of sensitivity to the feelings of others and to his single-minded dedication to achieve his own deliverance.

In his dealings with women, and often in his depiction of them in his works, Eliot is vulnerable to critics. Yet Lyndall Gordon disposes of some myths surrounding his relationship with his first wife, Vivienne, showing her to be a strong influence on his work but a neurotic character. Her eventual incarceration in a mental asylum, sometime after Eliot had left her, was the responsibility of her brother, although Eliot did nothing to oppose it.

Lyndall Gordon's attribution of specific identities to some of the women in 'The Waste Land' is more controversial. Ted Hughes, for one, saw all these women as one woman - the "essential female"; the desecrated "sacred feminine source of Love"; the feminine aspect of Tiresias who, according to Eliot is "the most important figure in the poem" and in whose physiognomies he grasped homologies of the women in his life.

Lyndall Gordon began, perhaps, by taking up Helen Gardner's suggestions, in The Art of T.S. Eliot, that, elements of Eliot's poetry recall episodes in his life, and that Eliot was a confessional and visionary poet. Gordon elaborates these views with great skill, in great details, and with meticulous care to stay close to her primary sources. She is acute in showing the persistence of Eliot's American origin both in his efforts to "make his life conform to the pilgrim pattern", and in the echoes of place and voice which occur in his poetry. It was fascinating to read, for example, that Ezra Pound noted the rhythms of the Bay State Hymn Book of early Massachusetts settlers in Eliot's early poetic quatrains.

Half-way through Lyndall Gordon's book, I began to doubt some attributions of specific biographical identities and events to parts of 'Four Quartets', and I turned to Helen Gardner for another point of view. Lyndall Gordon notes that Eliot once "confided to Helen Gardner that hers was the only criticism of his work that he could recommend to anybody". Certainly there are differences in interpretation, and I like Gardner's statement that "the poem is not an allegory" and that "precise annotation" may "destroy the imaginative power".

But time and again I found that Lyndall Gordon was aware of the hazards of reading Eliot's work as an allegory, and that she backed up her claims so well with Eliot's own remarks or with quotations from his other work, that her claims were valid. Her source references are acknowledged at the end of the text and arranged according to page-numbers, which have the advantage that a reader is not distracted by them but the predicament is, like me, readers may not discover them until they are absorbed into the book.

T.S. Eliot, an Anglo-American litterateur, was awarded Nobel Prize for literature in 1948 and he is still esteemed as the most trustworthy poet of modern English literature who movingly touched upon the pangs and double-binds that eclipsed the lives of people during the first few decades of 20th century.

The writer is a literary analyst for The Asian Age

The writer is a literary analyst for The Asian Age