Published: 12:15 AM, 20 November 2019

Why oratory matters ...

Oratory has since the beginning of civilised existence kept people in thrall. Shakespeare provided a clue to the riveting nature of speeches in his plays.

You think here of Brutus and Mark Antony in Julius Caesar, of the many ways in which they played with words to convince the audience of the justness of the causes they held dear. But that was literature. In life lived from day to day, through the vagaries of politics, oratory has often been raised to the level of art.

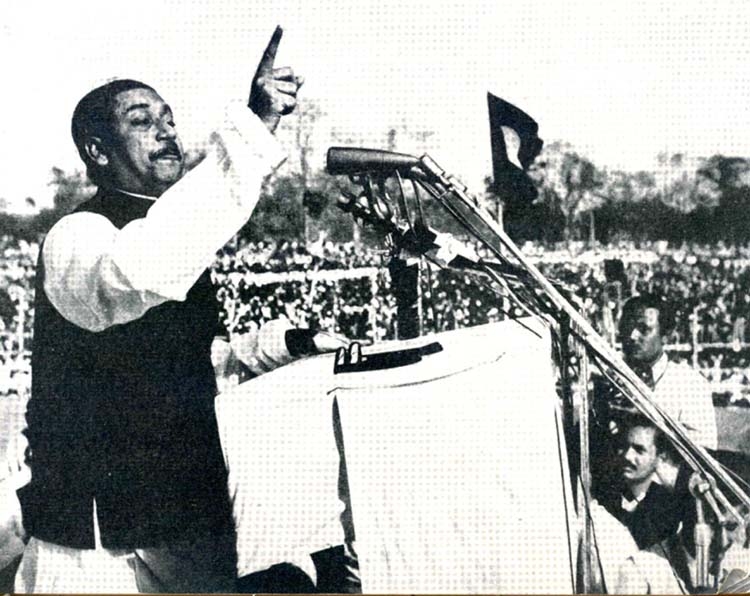

In Bangladesh's case, the speeches of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman were ammunition, over the years, in the defence of liberty. Gandhi was not a rousing speaker, but the calm religiosity he brought into his words drove the point home. And then there was Syed Badrudduja, whose command of Bengali, Urdu and English was demonstrated to huge effect in his speeches, particularly in pre-partition India.

We have before us this admirable tome of a work. In Speeches That Changed The World, a work with an introduction by the writer Simon Sebag Montefiore, it is a lost age, or many lost ages that once were steeped in idealism that come alive. You could argue with the editors, though, about the speeches they did not include in the anthology. Even so, there are all those specimens of the mind that recreate the past.

History buffs will not quarrel with the inclusion of orations rendered by men of divinity. Read here Moses, coming forth with the Ten Commandments ('Thou shalt have no other gods before me') as also Jesus with his 'Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven'. Muhammad too makes a desirable entry ('Turn your face towards the Sacred Mosque'), followed by the Sermon to the birds by St. Francis of Assisi ('My little sisters, the birds, much bounden are ye unto God').

A particular characteristic of speeches, good speeches (for there have also been millions of tedious ones), is the inspirational. That is how John F. Kennedy, otherwise a not very dynamic figure on the broad canvas of history, galvanised Americans through his inaugural address in January 1961.

'Ask not what your country can do for you', he declaimed, 'but ask what you can do for your country.' It is a speech much quoted by JFK fans around the world and yet it somehow loses its brilliance once there is mention of Abraham Lincoln. The Civil War-era American president was clearly a natural when it came to oratory.

The concluding words in his first inaugural address ('With malice toward none, with charity for all . . .') were a pointer to what was to be. And, true enough, it was with the Gettysburg address in November 1863 that Lincoln demonstrated the heights he could scale. 'Four score and seven years ago', he said with quiet insistence, 'our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.'

Great speeches come with a flavour of the literary; and Lincoln put literature in plenty into his speeches. Much a similar tenor was noted in Winston Churchill in his 13 May 1940 address in the House of Commons --- 'I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.' Words flowed, like a stream, from the wartime British leader.

In August of the same year, it was again an interplay of words that fired the patriotism of the nation when Churchill spoke of the sacrifices being made in the war against Nazism, 'Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.'

Oratory takes the collective imagination to new heights, as Jawaharlal Nehru demonstrated through his 'tryst with destiny' speech in the opening moments of a free India in 1947 ('At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom').

Blood was being spilled in the aftermath of partition, but that reality did not deter India's first prime minister from lighting the path to hope for his people. Contrast these sentiments with those that Eamon de Valera voices in April 1966 on the fiftieth anniversary of the Easter Rising.

His is an elegy, dedicated to the patriots he fought with once, all of whom were to perish in what for Ireland was an epic struggle for self-determination. In De Valera's words, 'they were all good men, fully alive to their responsibilities, and it was only the firmest conviction, the fullest faith and love of country that prompted their action.'

Speeches is fundamentally a journey through political experience straddling the globe. If there are the lofty perorations that find a place here, there are too the manifest lies that do not find an escape route. And thus, more than a year before he would get tangled in his venality, Richard Nixon tells Americans in April 1973 that 'there can be no whitewash at the White House.'

It was, in truth, a contaminated world that Nixon created, and lived in. Morality did not matter to him, but it did for Vaclav Havel, who tells the people of Czechoslovakia in 1990, 'We live in a contaminated moral environment.' That takes you back to the moral superiority that General George S. Patton personified in his times. His speech, wherein he vows, 'I am personally going to shoot that paper-hanging sonofabitch Hitler', is one of the items in this anthology.

The same holds true for Nelson Mandela, who defiantly tells the court trying him in apartheid-driven South Africa in 1964, 'I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities.'

And so the caravan of history moves on. Along the way, Charles de Gaulle finds his own place in it. As France falls to Nazism, he takes flight to London, from where he sounds the clarion call that would rejuvenate his dispirited country: 'France has lost a battle. But France has not lost the war!' Thoughts of war then give way to ruminations on peace, as in this placidity of a statement from Mother Teresa in 1979: 'Love begins at home, and it is not how much we do, but how much love we put in the action that we do.'

It is a moving kaleidoscope of the ages you have here. For sometime, you go beyond the mediocre, to recall a world once epitomised by sublimity, larger-than-life individuals. Remember Oliver Cromwell?

As he dismisses the Rump Parliament in 1653, he rails against the lawmakers: 'It is high time for me to put an end to your sitting in this place, which you have dishonoured by your contempt of all virtue, and defiled by your practice of every vice. . .' His voice rises to a crescendo, as he sends the legislators packing, 'Take away that shining bauble there, and lock up the doors. In the name of God, go!'

The writer is Editor-in-Charge,

The Asian Age

The writer is Editor-in-Charge,

The Asian Age